Importance of Getting Entire Team Involved in Estimation

- by Olumide Akerele

- •

- 16 Sept, 2018

- •

A well-established best practice is that those who will do the work, should estimate the work, rather than having an entirely separate group estimate the work.

But when an agile team estimates product backlog items, the team doesn’t yet know who will work on each item. Teams will usually make that determination either during iteration (sprint) planning or in a more real-time manner in daily standups.

This means the whole team should take part in estimating every product backlog item. But how can someone with a skill not needed to deliver a product backlog item contribute to estimating it?

Before I can answer that, I need to briefly describe Planning Poker, which is the most common approach for estimating product backlog items. If you are already familiar with Planning Poker, you can skip the next section.

Planning Poker

Planning Poker is a consensus-based, collaborative estimating approach. It starts when a product owner or key stakeholder reads to the team an item to be estimated. Team members are then encouraged to ask questions and discuss the item so they understand the work being estimated.

Each team member is holding a set of poker-style playing cards on which are written the valid estimates to be used by the team. Any values are possible, but it is generally advisable to avoid being too precise. For example, estimating one item as 99 and another as 100 seems extremely difficult as a 1% increase in effort seems impossible to distinguish. Commonly used values are 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, and 100 (a modified Fibonacci sequence) and 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 (a simple doubling of each prior value).

Once the team members are satisfied they understand the item to be estimated, each estimator selects a card reflecting their estimate. All of the estimators then reveal their cards at the same time. If all the cards show the same value, that becomes the team’s estimate of the work involved. If not, the estimators discuss their estimates with an emphasis on hearing from those with the highest and lowest values.

If you aren’t familiar with estimating product backlog items this way, you may want to read more about Planning Poker before continuing.

How Can Someone Participate Without the Needed Skills

Equipped with a common understanding of Planning Poker, let’s see how a team member can contribute to estimating work that they cannot possibly be involved in. As an example, consider a database engineer who is being asked to estimate a product backlog item that will include front-end JavaScript and some backend Ruby on Rails coding, and will then need to be tested.

How can this database engineer contribute to estimating this product backlog item?

There are three reasons why it’s possible--and desirable.

1. Planning Poker Isn’t Voting

When playing Planning Poker, participants are not voting on their preferred estimate. The team will not settle on the estimate that gets the most votes. Instead, each estimator is given the credibility they deserve. If one programmer wrote the original code that needs to be modified and happened to be in that same code a couple of days ago, the team should give more credence to that programmer’s estimate than to the estimate of a programmer who has never been in this part of the system.

This means that each team member can estimate, but that the team will weigh more heavily the opinions of those more closely aligned with the work.

2. Estimates Are Relative and That’s Easier

In Planning Poker, the estimates created should be relative rather than absolute estimates. That is, a team will say things like, “This item will take twice as long as the other item, but we can’t estimate the actual number of hours for either item.”

For example, this blog post contains one illustration. I provided my artist with a short description of what I had in mind for an image and he created the illustration. Most of my blog posts have one title illustration. Even though I have no artistic skill, I could estimate the work to create those illustrations as about equal each week.

Sure, some illustrations are more involved, and others can reuse a few elements from a past illustration. But most are close enough that I could estimate them as taking the same effort.

But some blog posts have two images. Even though I have no design skills at all, I’m willing to say that creating two images will take about twice as long as creating one image.

So a tester is not being asked to estimate how many hours it will take a programmer to code something. Instead the tester is estimating coding that thing relative to other things.

That can still be hard but relative estimates are easier than absolute estimates. And remember that because of point one above, the person whose skills may not be needed on the story will not be given as much credibility as someone whose skills will be used.

3. Everyone Contributes, Even If They Don’t Estimate

I want everyone on the team to participate in an estimating meeting. But that does not mean everyone estimates every item.

Despite relative estimating being easier than absolute estimating, there will still be times when someone will not be able to estimate a particular product backlog item. This might be because the person’s skills aren’t needed on that item. But that person may still be able to contribute to the discussion.

Sometimes the person whose skills are not needed on a given product backlog item will be the most astute in asking questions about the item, uncovering overlooked assumptions, or in seeing work that others on the team have missed.

For example, a database developer whose skills are not needed to deliver a product backlog item may be the one who remembers that:

The team promised to clean up that code the next time they were in it

There is an impact on reports that no one has considered

That when the team did a similar story a year ago it took much longer than anyone anticipated

and so on. The database developer may know these things or ask these questions even if unable to personally estimate their impact on the work.

A Few Examples

To provide a few examples, let’s return to role of a database engineer in estimating a product backlog item that has no database work. Here are some examples of things that team member might say that would add value to estimating that product backlog item:

- “I’m holding up this high estimate because this sounded like a lot of effort to code. It sounded like about twice as much as this other backlog item.”

In this case, the database engineer is making a relative assessment of effort. This will presumably be based on things said by coders. In some cases, the database engineer may be wrong in that assessment. But that doesn’t mean the person’s opinion is always without merit. The database engineer’s opinion should be given the merit it deserves (which may be great or little). - “Are you sure it’s that much work? I thought two sprints ago, you programmers were going to refactor that part of the system. If that happened, isn’t this easier now?”

Here the database engineer is bringing up information that others may not have recalled or considered. It may or may not be of value. But sometimes it will be. - “Are you sure it’s not more work than that? Have you considered the need to do this and that?”

In this case, the database engineer is pointing out work that the others may have overlooked. If that work is significant, it should be reflected in the estimate.

When Everyone Participates, It Increases Buy In

There’s one final reason why I suggest the whole team participate when estimating product backlog items, especially with a technique such as Planning Poker: Doing so increases the buy in felt by all team members to the estimates.

When someone else estimates something for you or me, we don’t feel invested in that estimate. It may or may not be a good estimate. But if it’s not, that’s not our fault. We will do much more to meet an estimate we gave than one handed to us.

We want everyone on a team to participate in estimating that team’s work. You never know in advance who will ask the insightful questions about a product backlog item. Sometimes it’s one of the team members who will work on that item. But other times those questions come from someone whose skills are not needed on that item.

So while not every team member needs to provide an estimate for each item, every team member does need to participate in the discussion surrounding every estimate. Teams do best when the whole team works together for the good of the product, from estimation through to delivery.

What Has Your Experience Been?

What has your experience been with involving the whole team in estimating product backlog items? Have you found it beneficial to have everyone participate even though not everyone has skills needed on each item?

I’ve never been a huge fan of horror movies. But I have always liked Halloween, especially as a kid. I loved dressing in a scary costume and trying to frighten my friends or other trick-or-treaters. And I admit to getting a bit of a thrill from walking through a well executed haunted house.

But, there are aspects to every agile transformation that can send a shiver down a spine--and those moments are not quite so thrilling. So let’s take the fear factor away from five things that might make you want to run for cover along your agile journey--first by naming them and then by talking about why they aren’t so scary once you understand how they work.

Eeek! Agile Has No Design Phase!

Architects and senior tech people are often frightened by the idea that there’s no design phase in agile. While it’s true that agile teams shun an upfront design phase, that does not mean that design doesn’t occur.

Design on an agile project is characterized by two attributes: it is both emergent and intentional. An emergent design is one that comes into existence over time. Rather than being done all upfront in a single phase, design is an ongoing activity. The design emerges through the creation of the software.

But design is also intentional. This means the design does not emerge randomly. Design is guided by the intent of the senior technical people on a project or perhaps even someone in a designated architect role.

If the senior technical people are concerned about a particular part of the system, the product owner should prioritize a product backlog item or two in that area. This will allow the team to explore that part of the system by building some small part of that system. Doing so will help identify the appropriate design in that area.

Allowing design to emerge guided by the intent of the team will reduce the terror of there being no design phase in agile.

Help! I'll Become a Generalist.

A common myth that has persisted since the earliest days of agile is that agile teams don’t value specialists and want everyone to become a generalist. This is frightening to many people for two reasons: First, no one enjoys all types of work equally and second because of the concern it could impact future employability if someone can do four things adequately instead of one thing extremely well.

The idea that everyone becomes a generalist on an agile team is completely false. If I’m coaching a team that has the world’s greatest JavaScript wizard, I’m going to want that superstar doing amazing things in JavaScript, not learning how to become a DBA.

Yes, agile teams value members who have multiple skills--the tester who can also write some JavaScript, for example. One of the easiest ways to balance the amount of work between two skills is to have someone who can do either type of work. If, for example, your team finds it hard to balance the amount of work in an iteration between programmers and testers, having someone who is adept at both coding and testing can solve that problem.

A goal in agile is the formation of cross-functional teams, which means the team has all skills needed to produce a finished, working deliverable within the iteration. Doing that does not require each person to have all the skills of a cross functional team.

If the thought of becoming a generalist makes your hair curl, understanding that a cross-functional team still allows for specialists should put your mind at ease.

Oh No! We Can’t Plan or Predict Dates!

Management is often chilled to the bone by the idea that an agile team can’t plan or predict dates further ahead than the current iteration or sprint.

Fortunately, this does not need to be the case.

Yes, agile teams give up the false comfort of overly planned projects with intricately drawn Gantt charts showing a precise completion date way in the distant future. But that does not mean agile teams are unable to make plans or predict future delivery dates or scope.

A huge benefit of agile is that every iteration the team turns the crank on the entire development process. That is, they take an idea usually expressed as nothing more than a simple user story, and they full implement that feature. This means that every few weeks, a team can measure its progress: They can know how much they got done.

Contrast this with a traditional development projects, perhaps one with an analysis phase, a design phase, a coding phase and, finally, a testing phase. When that team measures its progress over a period of time, they are measuring only how fast they are at doing one (or perhaps two) types of work. How fast a team is at doing design says nothing of how fast the team will be at coding and testing.

The key with agile planning is embracing the uncertainty--admitting that it’s impossible to know all the functionality that will be built before starting the project--and then adjusting for that in a variety of possible ways. When teams combine this realization with the ability to actually measure the amount of work done every iteration, it leads to reliable planning, which should calm the nerves of a management team daunted by the prospect of having no predictability.

Yikes! I Won't Have a Job!

The prospect of transitioning a team or company to agile is enough to scare the pants off some managers who are concerned they won’t have a job after the transition is complete.

This is understandable. It would be dismaying to start a transition effort aimed at helping a company knowing that it may make your role superfluous.

However, I can clearly say that I have never helped a company adopt agile and then seen that company say, “OK, we no longer need people with job title such-and-such. They’re all terminated.” It just doesn’t happen. Sure, a company may decide a specific job title is no longer needed or appropriate. But the individuals with those titles still have jobs. And in most cases, I believe they end up with better, more focused jobs. With that being said, it is true that some people will end up with less direct control over people or decisions and they may find that frustrating, even to the point of leaving the company.

But because I have never seen significant layoffs of any role or skill as part of transitioning to agile, I believe this fear is as misplaced as that of a zombie apocalypse.

Zoinks! Scrum Has Too Many Meetings!

Like many people, I really hate meetings. In fact, it’s largely why I do what I do. Most days I have no meetings at all. Pure bliss.

But even I can acknowledge that some meetings are important and useful. And that includes the four standard meetings of Scrum: the sprint planning meeting, the daily scrum, the review, and the retrospective.

The thought of all these meetings, however, can send some people into a cold sweat.

Here’s the problem with Scrum meetings--they have names. When something has a name, it’s easier to attack. In my experience, many teams who adopt Scrum had more meetings before Scrum. But the meetings didn’t have names and were mostly ad hoc meetings called to resolve specific issues.

Here’s an experiment I like and that you can easily do to see if you’re having significantly more meetings with Scrum. Randomly pick a month on your calendar from before you started adopting an agile approach. Open that month up in your calendar software and add up the time spent in meetings. Then add up the average time in your Scrum meetings and see how they compare.

Based on my experience, you might well be surprised by the results. But because those pre-agile meetings were not recurring, regular meetings, they didn’t have names and so they don’t stick out in our memories the same way a named meeting, like “Sprint Planning,” does.

The key for overcoming the terrorizing thought of too much time spent in meetings is keeping the meeting short. Occasionally I’ll work with a team that I need to encourage to spend more time in a certain meeting. But most teams spend too much time in each of the standard meetings. Once they find ways to shorten them, those meetings should no longer frighten us out of our wits.

Relax...those Ghosts and Ghouls Aren’t Real.

While it can be fun to walk through a haunted house or dress in a scary costume, most of us can easily remember that it’s all make-believe. Those ghosts, ghouls, vampires, werewolves, and crazed lunatics with chainsaws aren’t real.

And neither are the five agile legends I’ve outlined here. And while no one can be faulted for being afraid at first, education and experience will pull the mask off the myths, leaving us reassured rather than unnerved.

What Have You Been Afraid Of?

What part of transitioning to agile did you find the most scary? How did you overcome your fear? Please share your thoughts in the comments section below.

A common problem with user stories is how to add the right amount of detail to a story so that it is ready to be brought into an iteration or sprint.

It's an important balancing act. Bring a story into an iteration before it is sufficiently understood and there will be too many open issues for the team to complete it within the iteration. But try to resolve every open issue and add every little detail to a story and you end up with functionality that takes far too long to make it into the hands of users.

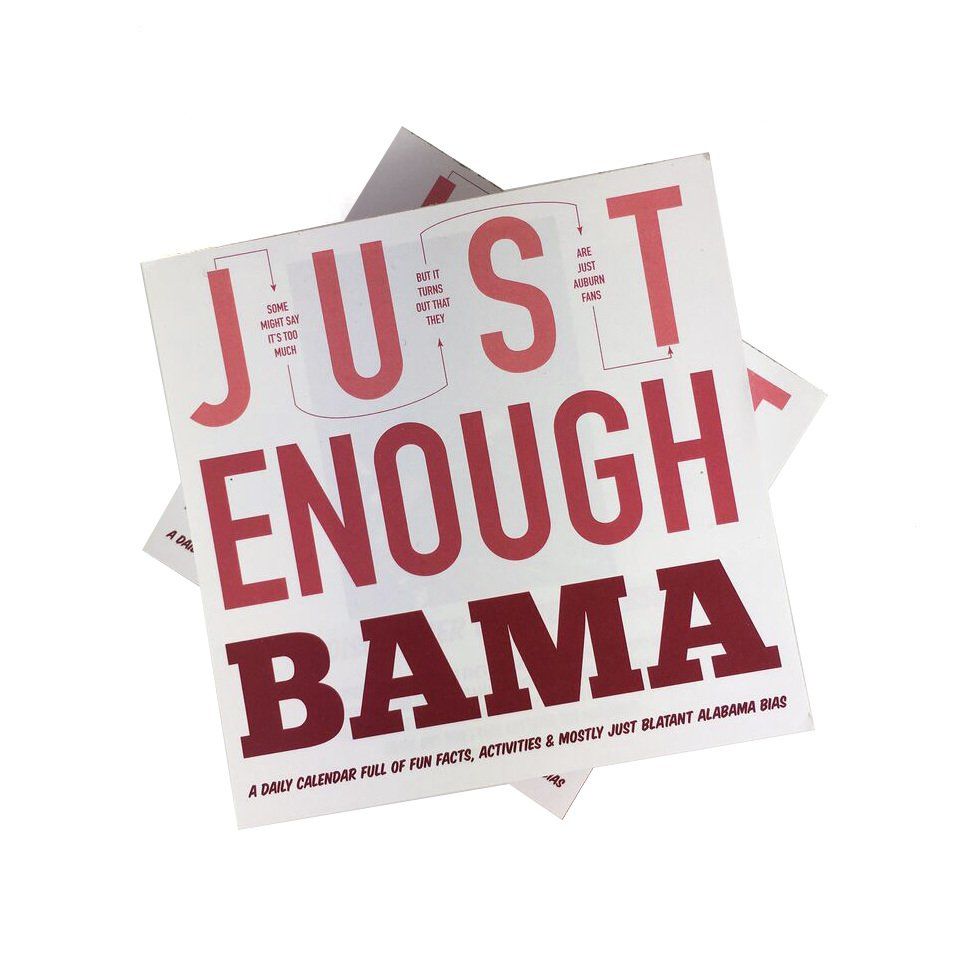

Like Goldilocks and the bears, we don't want stories with too little or too much detail. We want detail that is just right.

And we want that detail at just the right time, too. When detail is added to a user story is every bit as important as how much is added.. If details are added needlessly far ahead of when the story is worked on, there is a strong chance that some of those details will be wrong.

Trying to resolve all open issues in advance is costly. It can lead to rework if wrong answers are provided. It can lead to longer time-to-market as team members are stalled waiting for answers. It can also lead to a loss of creativity as programmers are merely told exactly how to implement something.

Not Everything Needs to Be Known Before Starting

When thinking about working on a user story, it is useful to realize that the team doesn't need to know everything before it starts a story.. All open questions need to be answered before a story is finished , but not all need to be answered before the story is started.

As an example, suppose a team is working on a story such as, “As a user, I am locked out after n failed attempts to log in.” The team clearly needs to know the number of failed attempts before they call this story done. But both programming and testing can begin without that answer.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or your team has ever struggled to include the right amount of detail at the right time, I’ve created a free 13-minute training video to help.

In it, you get concrete advice on how you can know the right amount of detail to add to each user story. I’ll also share with you the one question I ask in every retrospective to make sure detail is being added at the right time and in the right amount.

Watch now and see how to add the right amount of detail at the right time.

This is the third in a series of videos I’ve created to help you write better user stories. But it will only be available through 11 October. So if you’re like the majority of agile teams who struggle with adding the right amount of detail, go watch the video right now. I know you’ll find it helpful.

What’s Your Experience?

Does your team sometimes struggle to add the right amount of details at the right time to user stories? How do you ensure stories are neither too vague nor too detailed? After you watch the video lesson, please share your thoughts in the comments section below.

Isn’t it extraordinary that something as fundamental as emotion is only just finding its place in our world? Recent advances in understanding how human brains work have given us a new focus on emotion, showing us how it directs and influences us.

Skills to Build Relationships

“The trouble is that education is so academic,” Catherine begins, “It’s based on knowledge and not the ability to build relationships.” Aga too had highlighted that the skills needed in today’s AI driven world are those that differentiate us from robots. Knowledge can be accessed online or programmed in but thriving in a world that’s in a constant state of fast change needs the ability to collaborate and communicate effectively.

Research indicates that emotional intelligence is twice as important as IQ when it comes to getting where we want to go in life, and yet emotion is still largely ignored by our education system. “The gap is that we don’t learn about emotions at school,” Catherine continues, “Actually, teacher training generally doesn’t cover emotions at all. It’s a real omission. Emotions are the route to self awareness and self knowledge, and these things are critical for success.

“In schools emotions tend to be branded as a bit of an inconvenience. Children are encouraged to control their emotions, but they are not empowered to understand and respond to them. Think about it, a teacher may well implore a child not to cry, or they may say that a child shouldn’t be angry and apply correctives to prevent it. We are not taught to give space to emotion.”

Emotions as Warning Lights

Catherine uses an analogy of a car to illustrate how she sees the role of emotions. “If your car flashes a red warning light that the oil is low, you may find that very irritating. It doesn’t make you unplug the light to stop the flashing. You consider what is causing the alarm and most likely you then attend to the car’s needs, giving it what it is missing to restore the balance to its operations.

“This is the role of emotions in communication. They are our warning light system, and we ignore them at our peril.

“We are told that good communication comes from gaining congruence between what we think and what we say. Congruence is also needed with what we feel. We cannot ignore that bit.”

Telling a child “There is nothing to be scared of” teaches them to mistrust their own emotions. Generation Agile points to the need to build children’s confidence so that they trust their instincts and feel empowered to share ideas and innovate. Just consider how the common retort “Never answer back” may sow seeds that prevent the transparent sharing of ideas and collaboration in the workplace.

“Ultimately,” Catherine concludes, “We need to educate children for a world that we won’t live in. Change is so fast that we can’t yet imagine the challenges that they will face and the context that they will live in. Today’s children will be tomorrow’s workers, and need the skills now to be confident communicators, to be able to collaborate and explore new things without fear.”

Humans are social animals. The way we communicate, collaborate, and explore and innovate has defined our evolution so far. It will define our future too. No surprise then that Communication is one of the 3Cs of Agile Leadership and a core principle of Agile Project Management.

I’ve been working with a company to revamp their bonus and incentive structure as part of the organization’s desire to become agile. No matter how well designed and executed an agile transition is, if incentives remain in place that encourage non-agile behavior, that’s how people will behave.

In “Succeeding with Agile,” I referred to this as organizational gravity. Unless enough of an organization’s culture is changed in becoming agile, organizational gravity pulls the organization right back to where it started.

Improperly aligned bonuses and incentives are some of the biggest sources of organizational gravity.

Incentives and Bonuses Are Different

Before looking at how we can create proper bonuses and incentives, let me clarify the difference between a bonus and an incentive.

An incentive is a reward given to an individual or team for achieving a stated goal. An incentive is offered in advance and is meant to motivate behavior in predictable ways. When my youngest daughter was little, I told her that if she cleaned her room by 3:00 p.m., I would take her to see a movie. That was an incentive.

In contrast, a bonus is not stated in advance. Rather it is announced and given at the time something is accomplished. Again using my youngest daughter as an example, when she came home from school with a great grade on a test I knew she’d studied hard for, I told her we’d celebrate that accomplishment by getting ice cream. That was a bonus.

Incentives and bonuses are both rewards with the key difference being that an incentive is announced in advance whereas a bonus is announced on the spot.

Some Troublesome Rewards

Bonuses and incentives can work against the goals of agile. For example, rewards that single out individual performers discourage teamwork. I’ve seen these in the form of “Programmer of the Year,” “Team Member of the Month,” “Most Valuable Contributor” and more.

Other types of rewards encourage suboptimizing behavior. Many of us have stories about testers who were rewarded based on the number of bugs they found. This type of reward led one tester I met to log over 200 entries into the defect tracking system for a single bug.

The bug was simply that a value was being improperly calculated and displayed on the screen. But the product ran on four operating systems (the current and prior versions of WIndows and Mac OS X), eight different browsers (the current and prior versions of four browsers), and was supported in seven different languages. So one bug was reported on Firefox v59 on Windows 8.1 in French. The same bug was reported on Safari 6.2 on MacOS 10.8 in English, and so on.

Bug reports like this wasted everyone’s time. But that tester sure looked productive in the “Bug Finder of the Month” contest.

How About Money?

Financial rewards are almost always a bad idea. Financial rewards are often introduced by a well-meaning boss who wants a team to make a particularly aggressive deadline. The boss will offer an enticing amount to the team if they can deliver by then.

So far, so good. But the problems arise on the next project. On that, the team may start on schedule, but they’ve been trained that if they get a little behind (or perhaps even only if they report themselves as a little behind), the boss will offer a bonus. This becomes a dangerous cycle.

Besides, financial rewards don’t tap into people’s intrinsic motivations. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with money. Most of us wouldn’t show up for work without at least some paycheck. But we’d like to tap into deeper motivations than the purely financial.

The Team That Taught Me About Financial Rewards

I learned a lot from a team many years ago to whom I gave a large financial bonus. This was two teams of 12 developers, and I gave them a bonus of $75,000, which would be more than $6,000 per person … if I split the bonus evenly.

And that was the trouble. I had allocated the bonus in the budget, so I had the money as a pool to give them. But when it came time to decide how I would give it to the team, I couldn’t decide.

Should I:

- Give the same amount to each person? If I gave each person $6,000, that seemed unfair to those with high salaries and overly generous to others.

- Give an amount proportionate to each person’s salary? This seemed the opposite.

- Weigh the amounts by how many months the person had been on the project? It seemed unfair to give the same amount of money to a developer who joined the project a month ago as someone who had worked six months on it.

- Give to the developers who had worked on this project but had been transferred off? It seemed unfair to leave them out, but if they weren’t there during the hardest period, did they deserve as much?

I couldn’t decide. I went back and forth on this. Some of the key people on the project knew I was planning this bonus and wrestling with this decision. They offered advice. But each person’s suggestions were always very aligned with what would reward them the most.

And so, I gave up.

I told the team I would give them $75,000 but it was their decision how to allocate the bonus.

I told them the issues I’d been struggling with and said that whatever they decided would be fine. But they had to all agree on the process they’d use and the allocation.

A week after I shifted the problem to them, we had a team meeting. They told me they could not find a way to distribute the bonus money. They argued about it. And they felt the money was interfering with the strong bonds they’d built as a team.

And they gave the money back. They decided they didn’t want it.

I don’t think I’d ever been more proud of--or surprised by a team.

We ultimately decided to spend some of the money on a nice out-of-town trip for everyone plus a significant other. The rest was returned to the budget.

And it was the last financial reward I’ve offered a team.

So How Should We Reward an Agile Team?

So how should we reward an agile team? I think the most important consideration is that rewards should encourage teamwork rather than individual performance. I favor rewards (both incentives and bonuses) that are given to everyone on the team.

This doesn’t mean there’s no role for individual rewards. I think those can be fine, but for individual rewards, I prefer to make them smaller, at least in relation to team rewards.

For example, I’ve worked with a few product owners who carry five-dollar bills and give them to team members who could quote the project’s elevator statement or three main goals when asked. No team member’s life was improved by $5. It was more the knowledge that they passed the test when asked. More than one of these team members pinned the $5 to their cubicle wall.

Similarly, a handwritten note can do wonders in this era of constant email deluge. Take the time to write a note every now and then thanking a team member for something special and specific they did.

One of my favorite rewards for a team is time. TIme is something that everyone seems constantly short of. I’ve rewarded a team with time a couple of different ways, which have been consistently well received. For example, you can offer a team an incentive of a week off if they meet some delivery milestone.

Or if a full week off is too much, offer the team a week (or a sprint) where all work is of their own choosing. They can refactor old code the product owner has been resistant to approving if they choose. They can experiment with new technologies. They can catch up on reading if they want. Whatever they choose is fine.

Another option is to give the team knowledge. If they achieve some goal, send everyone to a conference. If appropriate, everyone goes to the same conference. That’s especially good as you can include some fun time before or after. Or, if it’s better, allow each person to pick their own conference to attend some time during the year.

One of tenets of Scrum is the value of getting work done. At the start of a sprint, the team selects some set of product backlog items and takes on the goal of completing them.

A good Scrum team realizes they are better off finishing 5 product backlog items than being half done with 10.

But why?

Faster Feedback

One reason to emphasize getting work to done is that it shortens feedback cycles. When something is done, users can touch it and see it. And they can provide better feedback.

Teams should still seek feedback as early as possible from users, including while developing the functionality. But feedback is easier to provide, more informed, and more reliable when a bit of functionality is finished rather than half done.

Faster Payback

A second reason to emphasize finishing features is because finished features can be sold; unfinished features cannot.

All projects represent an economic investment--time and money are invested in developing functionality.

An organization cannot begin regaining its investment by delivering partially developed features. A product with 10 half-done features can be thought of as inventory sitting on a warehouse floor. That inventory cannot be sold until each feature is complete.

In contrast, a product with 5 finished features is sellable. It can begin earning money back against the investment.

Progress Is Notoriously Hard to Estimate

A third reason for emphasizing getting features all the way to done is because progress is notoriously hard to estimate.

Suppose you ask a developer how far along he or she is. And the developer says “90% done.”

Great, you think, it’s almost done. A week later you return to speak with the same developer. You are now expecting the feature to be done--100% complete. But the developer again informs you that the feature is 90% done.

How can this be?

It’s because the size of the problem has grown. When you first asked, the developer truly was 90% done with what he or she could see of the problem. A week later the developer could see more of the problem, so the size of the work grew. And the developer is again confident in thinking 90% of the work is done.

This leads to what is known as the 90% syndrome: Software projects are 90% done for 90% of their schedules.

Not Started and Done

In agile, we avoid the 90% syndrome by making sure that at the end of each iteration, all work is either:

- Not started

- Done

We’re really good at knowing when we haven’t started something. We’re pretty good at knowing when we’re done with something. We’re horrible anywhere in between.